Prologue: A Place of Ontological Uncertainty

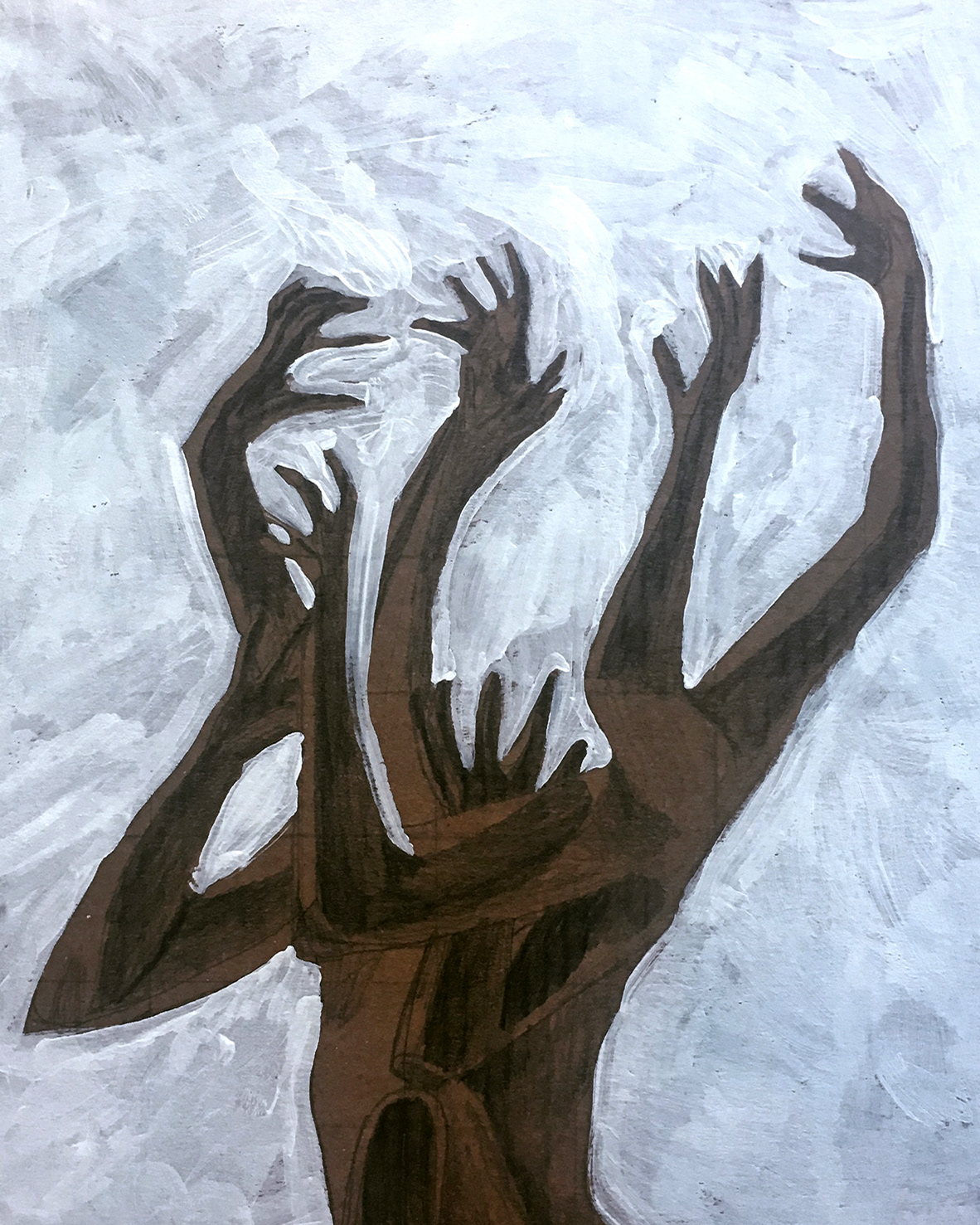

I would like to begin with what a philosopher could describe as a moment of ontological uncertainty: when you find yourself in a place where you know no longer what is real. You think you know where you are, but something is off. You could swear that this is the place you have previously visited, but structures that have previously formed its context are now missing. And since we are talking here about structures of enormous scale – ones that simply cannot go missing overnight – you start to question if this really is the place. Or if your own presence is real, if you are dreaming instead.

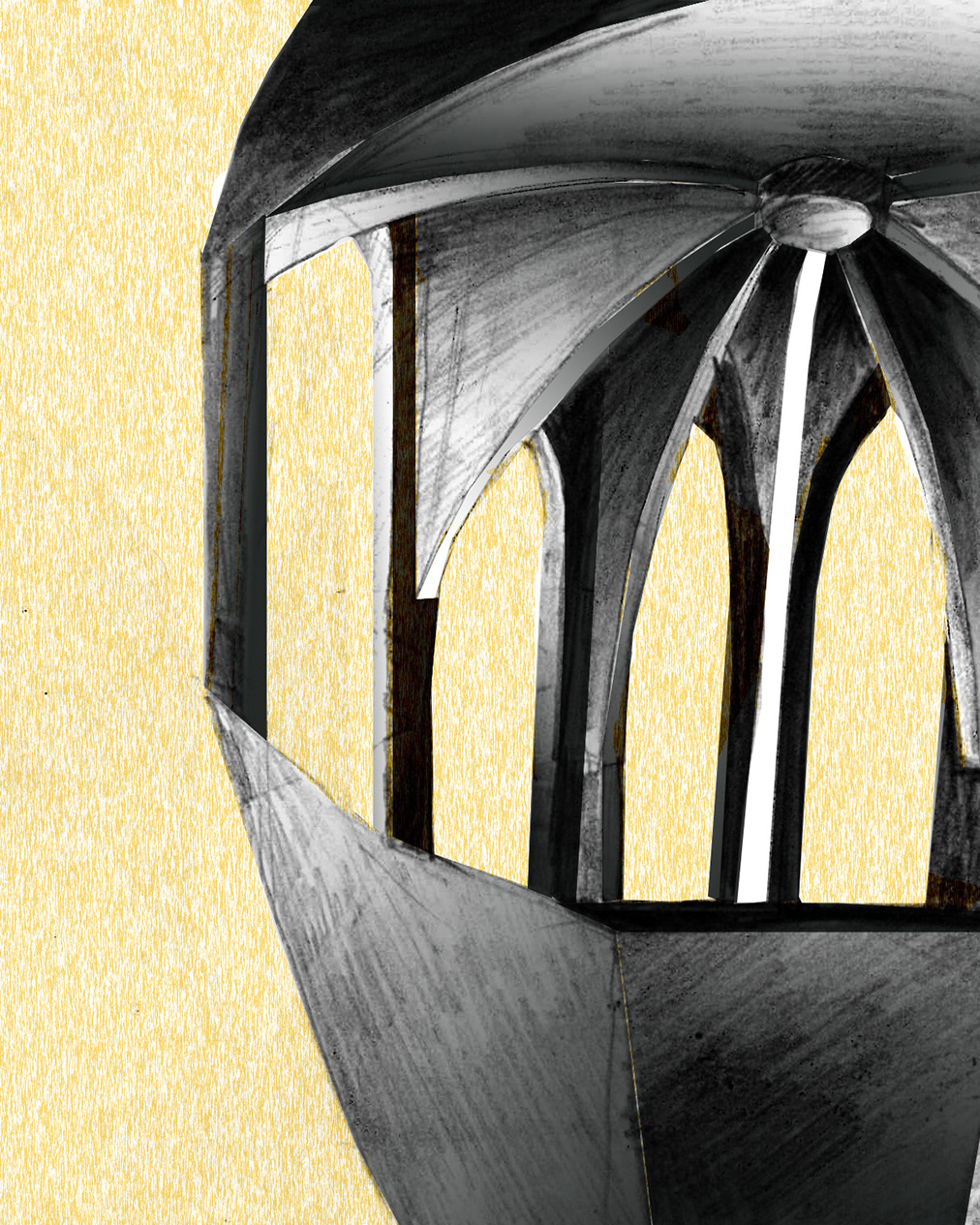

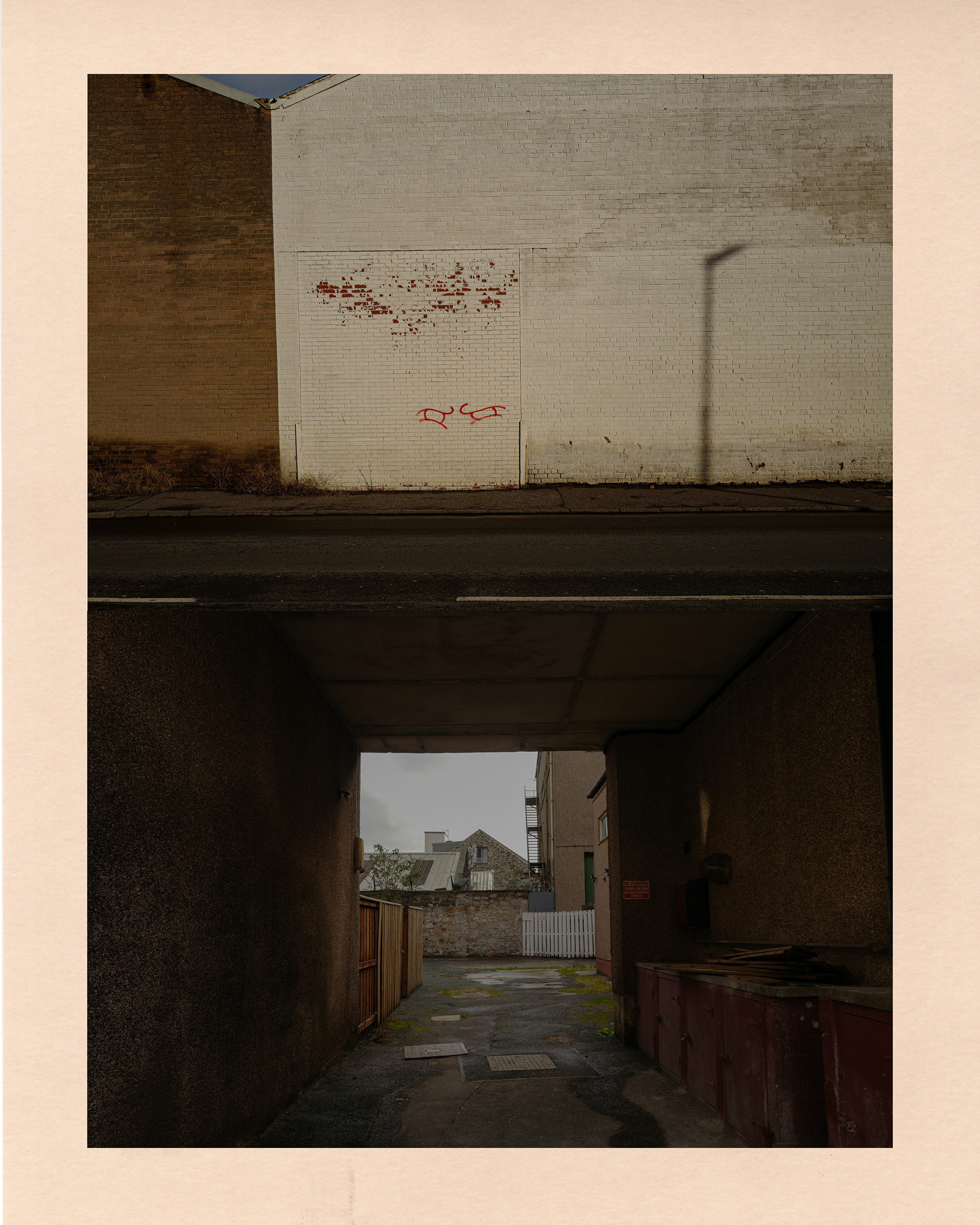

When I first entered the site of the Port of Leith on the 4th of October 2021, I saw an ongoing demolition of a gigantic grain silo. The structure stood still, half eaten by a heavy demolition plant. Wounded – but dominating, setting spatial order for much of the port.

I then re-visited the site on the 17th of April this year, during an unusual full moon phase, when a powerful away tide allowed me in for the last time, around the fence, over what is normally the sea bed. This time I felt immediate disorientation. As someone who thought that knows the site well, I was suddenly uncertain of where exactly I am. Looking at buildings – knowing they should be real – but also doubted myself, as their situation was radically different. Big buildings do not disappear so quickly, do they?

What happened between these two visits is, in a way, unimaginable to me. I would also attempt a generalization – I think it would be unimaginable for many architectural students of my generation. We are used to thinking of down-takings as almost surgical gestures. Extensive demolitions have been relegated into the past, either framed as grandiose mistakes of Modernist utopia or belonging to faraway war zones. It is why images from Mariupol are such a shock for us. It is also why it is hard to understand such destruction taking place in a contemporary Northern-European city.

This project re-imagines the Port of Leith as an architectural attempt to resist forces of what Andrew Herscher and Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi termed Spatial Violence. As a form of systematic violence, covert and deeply embedded in urbanism’s mode of operation, Spatial Violence manifests through physical destruction of the site and planning decisions guided by the mono-focal interest of capitalist values. It is not mere destruction of material, but of relationships (social, economic, aesthetic and ethical) that this material affords.

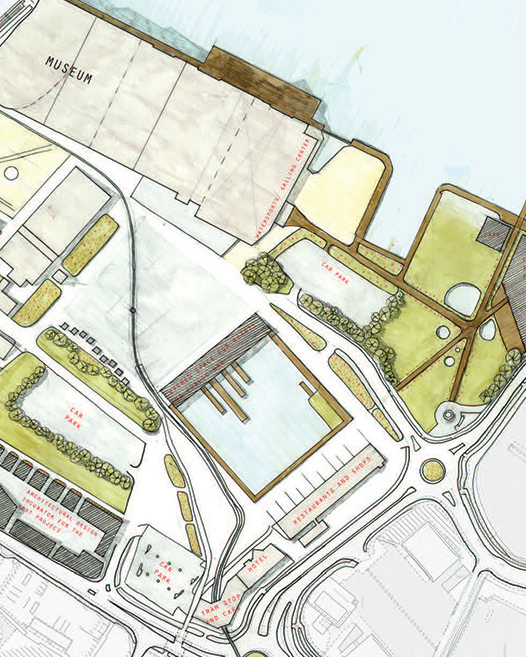

In contrast to these, this project seeks to analyse the context of Leith (specifically the site of Port) on a multi-layer basis:

Its current state.

Its histories.

Leith's relation to Edinburgh.

Its potential to institute a novel architectural imaginary.

Location.

Its current state.

Its histories.

Leith's relation to Edinburgh.

Its potential to institute a novel architectural imaginary.

Location.

Although located only 4 kilometres from the Edinburgh city centre, the site seems to belong to a different reality. The idiosyncratic character of the place is a result of its multiple layers – its history, fluctuations of its shape, its past and present functions and the way it is treated by the presence – fenced, out of sight and undergoing spatially violent destruction. Behind the fencing, an alternative world exists and it is different to the one that we know. The world – hidden and enclosed.

It is difficult to describe how satisfying and emotional was to discover its secrets and re-imagining it to speculate over the significantly different alternatives.

The East Sands Beach – once full of entertainment is now detached from the city and hides peculiar sea-sculpted boulders made of demolition parts. The man-made pieced treated by nature once again to demonstrate the ever-fluctuating borders, the mixing of elements and particles and the infinite number of possibilities.

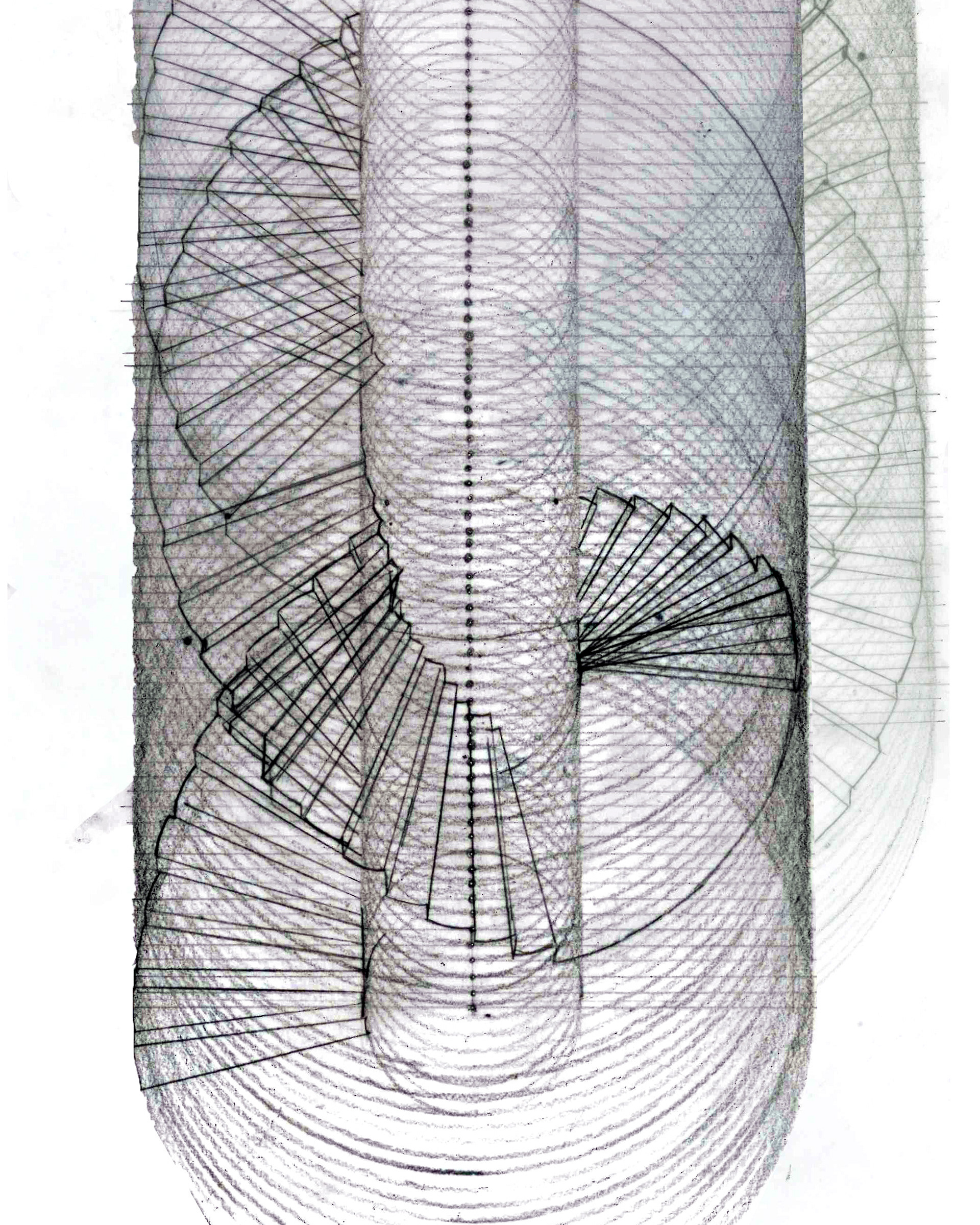

Once the site of the port held what Walter Benjamin called the condition of urban porosity, of tightly-knit spatial inter-dependence, temporal fluidity of space. As observed by an architectural thinker Andrew Benjamin, in his reading of Walter’s work, porous places such as the Port of Leith, have an infinite potential in their ‘’grey’’, often unseen parts. The porosity in the form of time and movement of people re-works the borders created by cartographies and politics and allows for ‘’organic’’ urban mixing. The borders are dynamic and fluctuate like the sea edge with its tides and currents.

There is only one condition – the borders need to be undone, which is only possible when we allow for organic mixing and remove the fences and the locks.

Virilio saw borders as a sign of the world in a constant state of combat. The creation of land boundaries and divisions, privatisation and enclosures are other faces of spatial violence, which we can observe in the port of Leith. We live in a divided, fragmented, conflict-prone world, where the rights of private property and profit are of the highest importance. The boundaries are unavoidable – they can be physical and spatial, which also applies to a tenement door, a bridge and a river. They can be conceptual and metaphorical – places can be divided by their names or general character.

They can be historic – the lines of the past that once used to cut the land and now are only marks of time – memories like the old train tracks. My thesis advocated liquid boundaries over fencing. It advocated the boundaries that encourage the porous formation of the place and allow the time and the movement of people to play a key role in their formation.

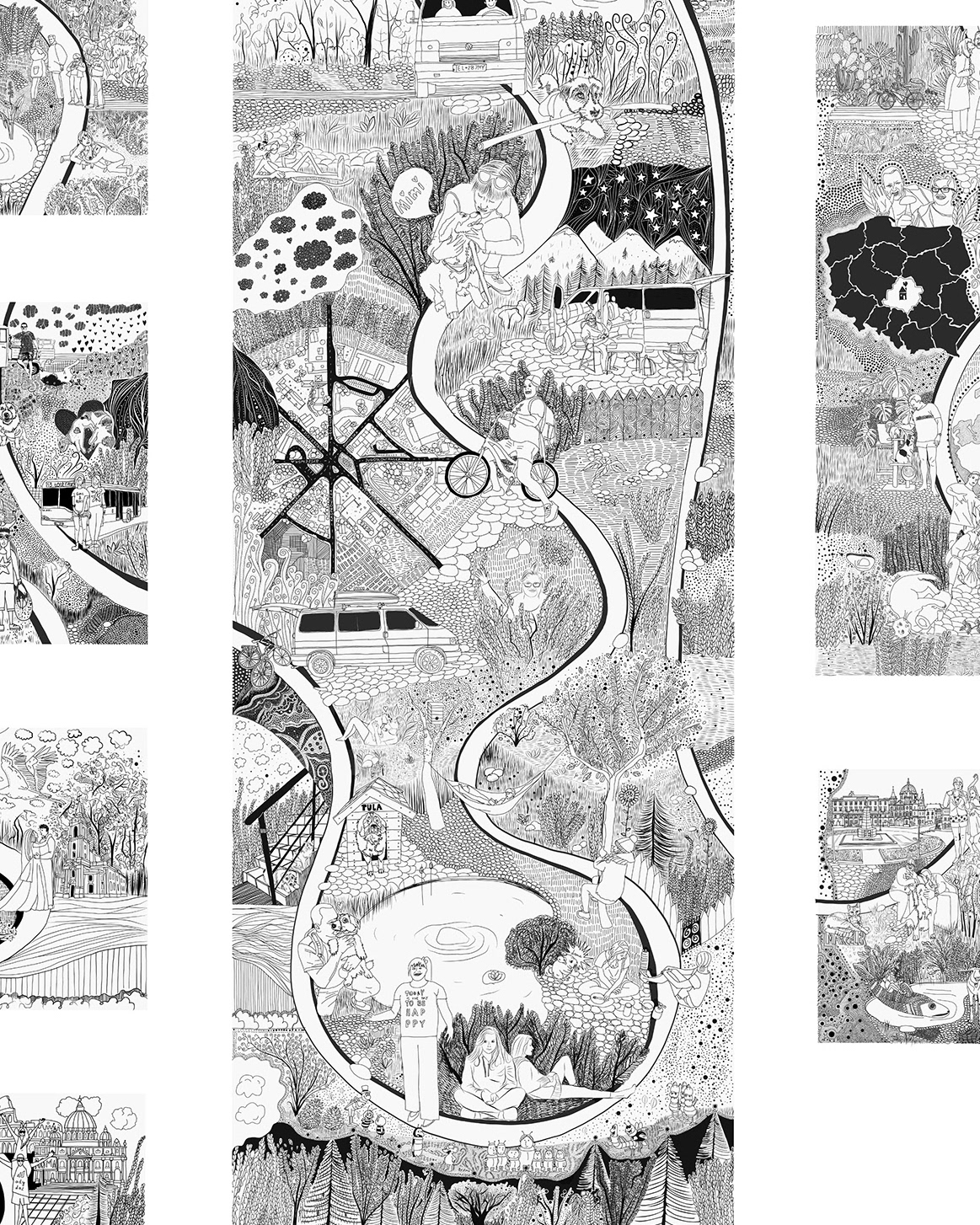

The project developed to be a collection of various fragments put together as a theoretical-imaginary assemblage.

First – as a collection of layers that formed my understanding of the architectural world I created.

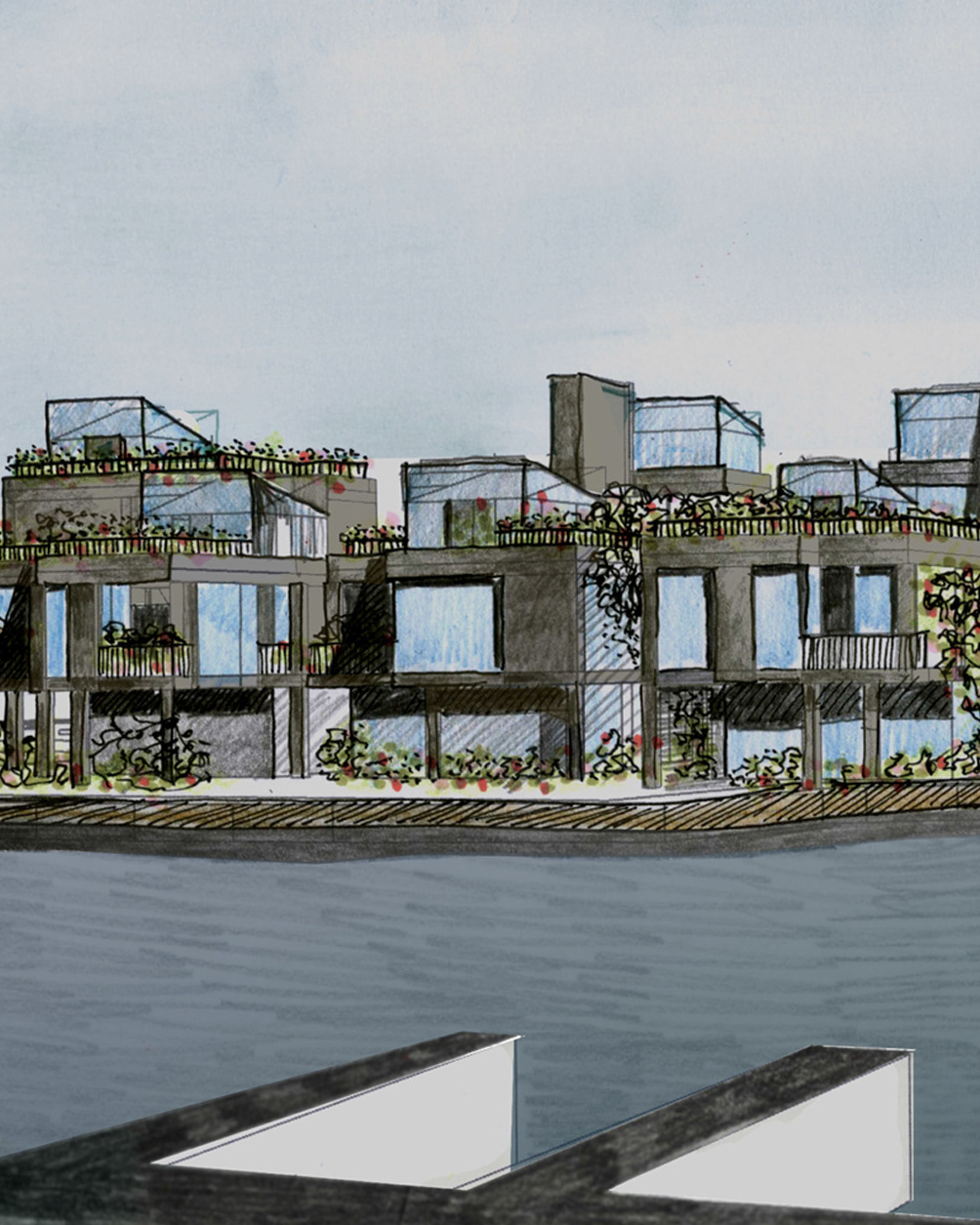

Second – a collection of perspective moments that zoomed into the new alternate reality. The views are representations of the unstable ontological status of the site. They are not placed in any time frame as they render as material not only the still-existing elements but also imaginary architectural imageries and the particles from various past moments.

The latter – including the past – is a tribute to the cultural value of the historical footage existing in the Port of Leith, which might not be seen as ‘’heritage’’ today, but in my view should be given a chance to last. Ungrounding places amounts to the erasure of history and promotes the development of soulless, generic imaginaries of the future.

Being an assemblage of speculative fragments and moments, my thesis attempts to offer a critique of a totalising approach of current planning policies.

Exchange matter(s)

One of the guides in the development of the new Port of Leith was a constant reference to the relationship of the site with its context and with, located slightly further, the city of Edinburgh.

The relationship between Leith and Edinburgh was a crucial element in the development of both settlements. However, increasingly Leith has grown dependent on Edinburgh. This is where we can start thinking about spatial violence, as seen in dictating the planning strategies for Leith by the Edinburgh local government. Furthermore, with the decline of the industrial era, the port area’s decay began. Today the site is under silent, but persistent forces of destruction, a form of ‘’urban cleansing’’ that considers the Port’s existing infrastructure and archaeology as insignificant.

The plan, we surmise, is to propose a series of generic urban blocks that belong neither to Leith’s nor to Edinburgh’s cultural and architectural character.

In contrast, in the architectural imaginary I created as part of this thesis, Edinburgh and Leith exchange their urban fabric to engage in the dialogue with each other. Edinburgh literally returns something of its urban fabric, its urban patterns and even specific architectural objects to the seemingly ‘empty’ site of the port. On the other end of the speculations, the Port of Leith offers some of its spatiality and ‘’emptiness’’ to the city of Edinburgh. The field for this exchange is a cartographic archaeology of both cities performed through drawing.

While this may be foreshortened as an attempt at offering ‘spatial justice’, the deeper point of this radical trans-contextualisation is to materialise, albeit in an imaginary way, the closeness of Leith and Edinburgh as two urban bodies that are of each other’s making. Perhaps by restoring this closeness we may begin to disrupt the forces of spatially violent destructions that both Edinburgh and Leith face.

I developed the work looking at the site at various scales, zooming in and out again. Understanding the place as a whole, I focused on its particular elements, with which I experimented through the mean of drawing and design. This alternative world is an expression of the site’s potential to institute a novel architectural imaginary, rooted in its characteristics, context and history and truly open the unexpectedness of the future.